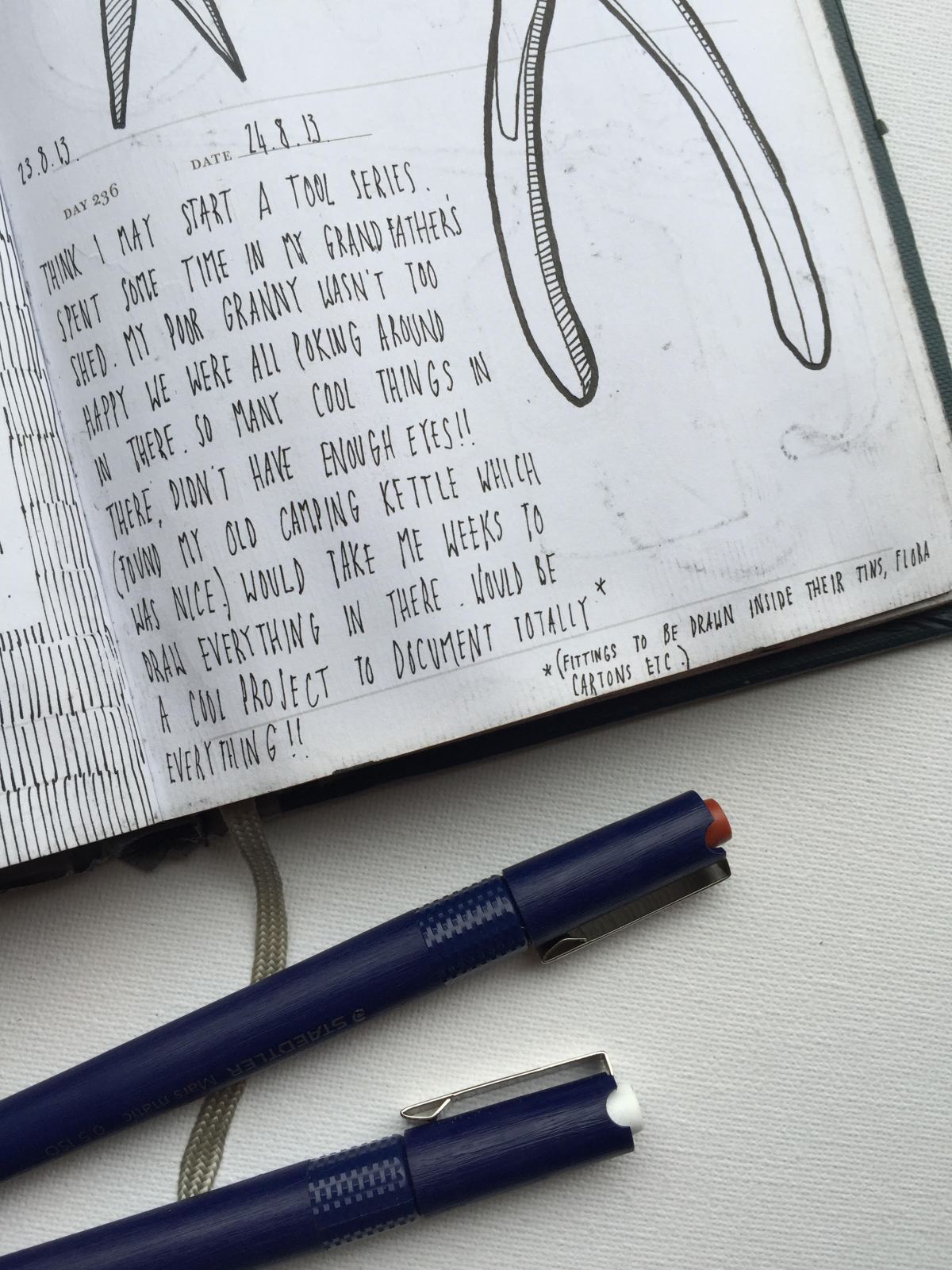

In 2013, artist Lee John Phillips challenged himself to one drawing a day—on top of the work he was doing as an art instructor. On day 236, Lee found himself inside his grandfather’s shed in southeast Wales. More than a decade after his grandfather had passed away, Lee discovered thousands of objects that had had hardly been touched inside the shed. He selected a few tools and sketched them inside his book.

At the start of the new year, Lee decided to begin a new one-a-day drawing mission; This time he focused entirely on his grandfather’s shed. Day after day. Paper and ink. Simple drawings. One object and then the next. But, not long after he cracked the spine of that book–only twelve days, actually–he recognized the limitations of one drawing or even the size of his sketchbook’s paper. And so, he left the book behind to draw more and at scale.

Frustrated by his life inside academia, Lee went on sabbatical in March 2014 and dedicated himself to the shed and his grandfather’s collections. He planned on drawing every day and to make his way through the entire shed. At first, he estimated there to be 5,000 objects in the shed and gave himself three years to handle and draw each item: jam jars and random cans filled with nails, screws, nuts, bolts, and items Lee couldn’t identify; manufactured tools and homemade tools to solve very specific problems; electrical supplies, spare parts, and the odd object or part that found its way from the house to the shed. Lee returned to his grandfather’s shed, not only to draw objects, but to connect to this space that physically and metaphorically represented the men in his life and to further understand the man who encouraged him to draw and with whom he shared patience, extreme focus, and a quiet nature.

“My family is predominantly male. My father is a steel fabricator. My brother is a plummer. My other brother is an engineer. My uncles are scaffolders, builders—it’s all manual labor. I was the first to go to university, of the blokes. I’m a vegetarian educated in the arts. For me, it’s quite bizarre to be so detached from that, from them. But the shed, the garage, is really a man’s spot. That said, I feel equally at home making things as I do drawing them, but to not do this as a career…

“I’ve given myself some rules because it was quite difficult to decided upon the process, how I was going to do this. So, first, if I pick it up and I rub it in my hands, and it doesn’t crumble, then I’ll draw it. Because there’s lots of bits that are chunks of rust and grease and things like that. cobwebs and matted bits of dirt. I thought, where do I draw the line? So, I started off with that as a rule. The second rule is: if the container or the carton or the packaging has already been opened, then I’ll empty it, draw everything inside, and then I’ll put everything back in it’s container and then draw it full. And then, the third, if the packaging was never opened by my grandfather, then I would draw it unopened. I would draw it as is. I wouldn’t open it and take the contents out. And, the last rule is, if there are multiples—if a jam jar has like 600 of the same nail—I’ll draw every single one.

Quite early on, I noticed, even with the multiples, every single one was different. They would rust differently. There were very very slight discrepancies in manufacturing, so I thought: everything is different. Again, all of equal importance, so I made the decision quite early on to draw everything.”

“A lot of the work I do is back at my parents’ house, sitting at their kitchen table. My dad will wander past and have a little look at all of the items I’m drawing—it could be a tin full of completely miscellaneous, random objects—and my father can almost always identify each one of those objects. There could be hundreds of them in there and knows what they were used for, and even if it was something that’d been modified, he could tell me what kind of a job they were doing at the time that required that particular modification of that tool or fixture. It’s sweet to see my parents relate to the object, and give me a bit of history, as well. One of the items, I remember, stopped my mum in her tracks. It was a little tin window from a dolls house. It was a dolls house my grandfather had made her. And, she’d not seen that little window in fifty years. She was stopped in her tracks. And, although it was lovely for me, it was all very sad.”

“A lot of it has to do with solitude and patience, being completely happy with your own company. For a long time my grandmother has said I’m like my grandfather. I’m quiet and patient and in a room of people, I’m happy to be in the background.”

This month–October 2015–Lee says he’s decided to drop the timeframe to complete The Shed Project. “I’ve opened tins and boxes, but I don’t know how many things are in there. I now estimate there to be around 80 to 100 thousand items. And, I’m almost at five thousand. So, I’ve got some ways to go.” On good weeks, Lee draws up to twelve hours a day.

Based in Pembrokeshire, Wales, LEE JOHN PHILLIPS has been teaching art for ten years. He diligently keeps up with his own creative practice and has been selected for shows such as Welsh Artist of the Year, Kyffin Williams Drawing Prize, and Jerwood Drawing Prize. He holds a Master of Arts in Visual Communication from Swansea Institute of Higher Education. Lee would very much like to spend a little more time outdoors than he is at present. (@LeeJohnPhillips)

Based in Pembrokeshire, Wales, LEE JOHN PHILLIPS has been teaching art for ten years. He diligently keeps up with his own creative practice and has been selected for shows such as Welsh Artist of the Year, Kyffin Williams Drawing Prize, and Jerwood Drawing Prize. He holds a Master of Arts in Visual Communication from Swansea Institute of Higher Education. Lee would very much like to spend a little more time outdoors than he is at present. (@LeeJohnPhillips)