A blurry, 8×10 black-and-white photograph of our golden retriever taken for a seventh grade photography class, mounted on a pink mat. My dad hung the photo in his closet, above his tie rack, soon after I took it. Or maybe I forced him to do it. It hung there for more than two decades, long after the dog died and I’d abandoned black and white. The focus on the curly hair framing our dog’s face is exquisite.

**

My dad’s first real sickness was also his last. Diagnosed with stage 4 colorectal cancer in late June 2013, he was gone in September. Scan, diagnosis, chemotherapy, false hope, hospice, morphine, death. Two months, six last-minute flights across the country from Wisconsin to Seattle. In the end, my presence couldn’t save him. The person I saw in the hospital that summer, or at home struggling to sit up and unable to eat, never felt like my dad. Even the decision to stop the treatment, which had no chance of arresting the spread of death, felt like it was made about another person who couldn’t possibly be the same man I talked to on the phone almost every day, since leaving home for college sixteen years ago.

**

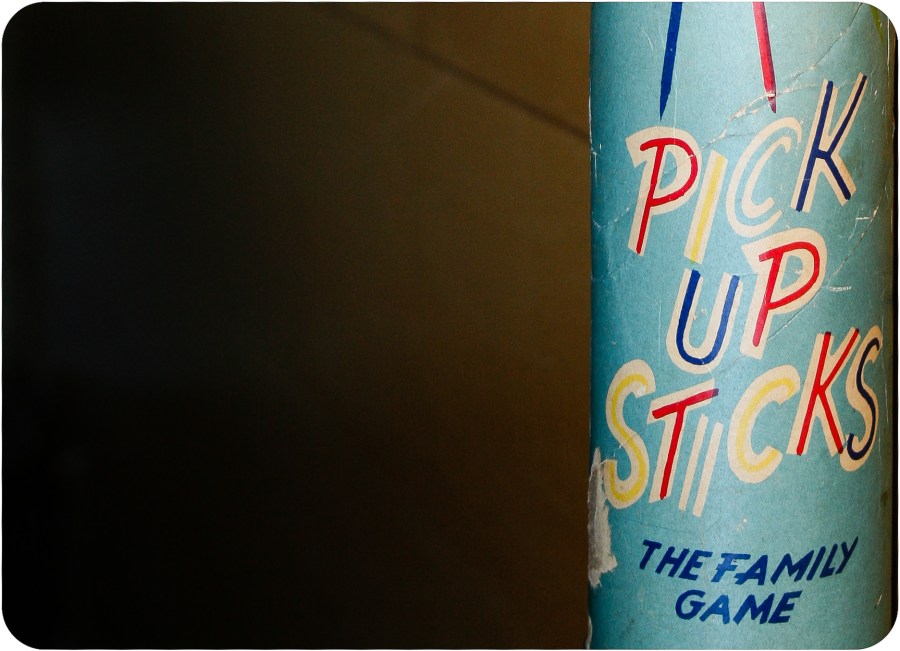

A tube of 1950s Pick Up Sticks from the Lido Toy Company. I grew up in a games-hating household—games were what you did when the power went out for days and you had nothing else to do. This was the only game my dad ever wanted to play. And though we had several different sets, this is the only one we used. I usually won. The last time I didn’t win was the last time my dad ever played.

Sons are supposed to grieve their fathers most; daughters their mothers. Somehow, in our culture, daughters can be “daddy’s little girl” until at some indeterminate point that only reveals itself when he’s gone. But your mother’s loss is the most terrible loss of all. That’s what all the grief books told me. I haven’t lost my mother, so I can’t say. Fatherless sons lose their model of manliness, of manhood. But what do fatherless daughters lose?

**

Wooden Thai sculpture. I never thought I looked like my dad until he went to Thailand for three weeks in the summer of 1993. My mom and I got up at 7 a.m. each day to call him there on the other side of the world, his day ending while mine had just begun. When I sat in the hairdresser’s chair, staring at my thirteen-year-old self in the mirror, I saw my dad’s eyes looking back at me.

Much of disease is waiting. Waiting for blood draws, test results, procedures, doctors. Some days, I swallowed my hunger for hours so as to not miss the doctor. We knew only that she was coming, but not when. I drew pictures of planets and trees on the white board beside his bed. The nurses seemed charmed by them until they learned the daughter who drew them was not eight but thirty-three. Days seemed to stretch on without end, but the individual hours passed quickly and unnoticed. Morning and then suddenly night, and it was time to go home before another day of stillness. We waited for the disease to really happen, to get there, to really take hold. And then we waited for my dad to die.

**

This Old House t-shirt. Sunday afternoons revolved around This Old House as far back as I can recall. From Bob to Steve to Kevin. We liked the carpenter Norm best, but who doesn’t? The t-shirts my dad loved for years are now the ones I wear to bed, comforted by the life still in them.

My dad was not perfect, and I wasn’t the ideal daughter. I spent much of the last year of his life angry that he had not done more to take care of his own mother as she was bilked by relatives I’m shocked share my blood. I thought I would never forgive him. But of course, the moment my dad was diagnosed, devastation replaced my anger. Our fights always happened this way: angry and bickering for a few explosive minutes, and then we were fine.

**

AE-1 camera. My dad collected old cameras, but this is the one I wanted. In junior high, I signed up for two photography classes (see the blurry photo of the dog, above). He allowed me to use his camera begrudgingly—“It’s my homework, Dad! What do you want me to do?”—but he watched my every f-stop.

Grief does strange things to you. When older people who have lost a parent try to reach out and tell me they understand, I appreciate the sentiment. But I think, they can’t possibly understand what I am experiencing. Even as I nod my head over our shared plight, I internally scream, “But your parent was old. Did you think they were going to live forever?!” My dad was young, just a year into his retirement and with big plans to travel. But of course, death and pain don’t care. No matter how old you are, he’s still your dad and you’re always his child.

**

I’m now the owner of several things I never wanted to own. And yet I wanted them all the same. I look at them and wonder if they say more about me than they do about my dad. What would he think if he saw the pieces of his life I chose to transport 2,000 miles across the country?

When I was a kid, my dad accused me of copying him, a characterization I loudly rejected. No kid wants to be like her parent. But my dad always got me when no one else did. I never needed to explain why we had to visit the Mustard Museum when we were supposed to be looking at potential graduate schools, because he’d marked it on his “to visit” list, too. Together, we toured dozens of state capitols, a vinegar museum, the Corn Palace, and once in Argentina, a museum dedicated to plumbing fixtures. The line between us, where I begin and my dad ends, seems hazy at best.

And the same is perhaps true of this stuff now, as none of it belonged to my dad alone.

ERIKA JANIK is the author of five history books, including Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine. Her work has appeared in Smithsonian, The Atlantic, Salon, Mental Floss, and Edible Milwaukee, among others. By day, she is the executive producer of the radio series Wisconsin Life on Wisconsin Public Radio.

ERIKA JANIK is the author of five history books, including Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine. Her work has appeared in Smithsonian, The Atlantic, Salon, Mental Floss, and Edible Milwaukee, among others. By day, she is the executive producer of the radio series Wisconsin Life on Wisconsin Public Radio.